Harmony

Harmony is the source of manifestation, the cause of its existence, and the medium between God and man.

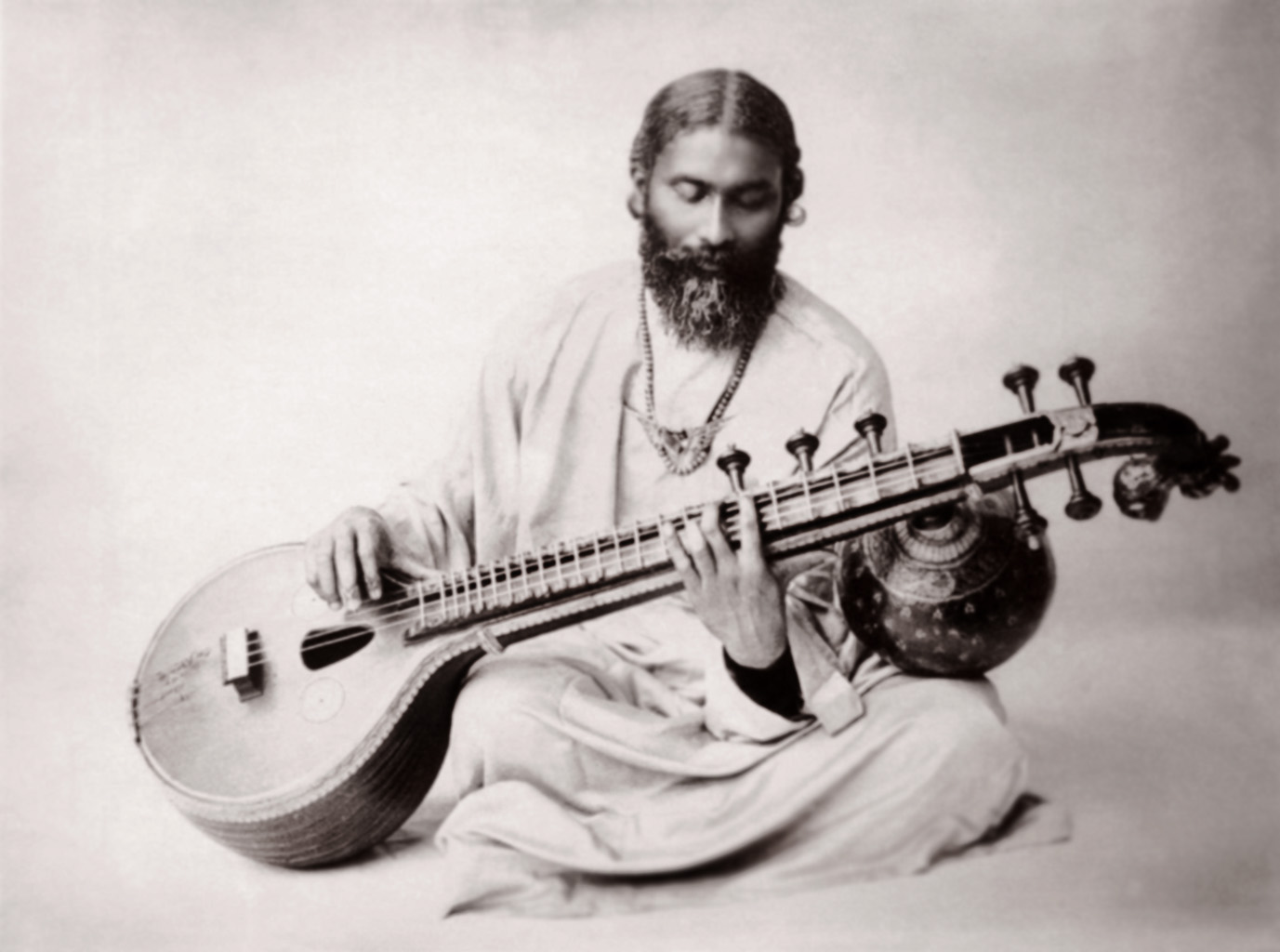

Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan

Harmony is the source of manifestation, the cause of its existence, and the medium between God and man.

The peace for which every soul strives, and which is the true nature of God and the utmost goal of man, is but the outcome of harmony. This shows that all life's attainments without a sense of harmony are but vain. It is the attainment of harmony which is called heaven, and it is the lack of it which is termed hell. The master of harmony alone understands life, and he who lacks it is foolish in spite of all other knowledge that he may have acquired.

The Sufi gives great importance to the attainment of harmony, believing that light is for angels and darkness for the devil, but that harmony is necessary for the human being in order to keep a balance in life.

There are three aspects of harmony: eternal, universal and individual.

Eternal harmony is the harmony of consciousness. As it is in itself eternal, all things and beings live and move in it; yet it remains remote, undisturbed and peaceful. This is the God of the believer and the God of the knower. All vibrations, from the finest to the grossest, as well as each atom of manifestation, are held together by this harmony. Both creation and destruction take place in order to uphold it. Its power ultimately attracts each being towards the everlasting peace.

Man is drawn in two opposite directions by the power of harmony: towards the Infinite and towards manifestation. He is less conscious of the former than of the latter, and by facing towards one direction he loses sight of the other. The Infinite being, the essential spirit of all, finally attracts all to itself. The Sufi gives the greatest importance to harmony with the Infinite, which he realizes through resignation to the will of God, the Beloved.

The existence of land and water, the land for the water and the water for the land, the attraction between the heavens and the earth - all demonstrate a universal harmony. The attraction of the sun and moon to each other, the cosmic order of the stars and the planets, all connected and related with each other, moving and working under a certain law; the regular rotation of the seasons; the night following the day, and the day in its turn giving place to the night; the dependence of one being on another; the distinctiveness, attraction and assimilation of the five elements - all prove the universal harmony.

The male and female, beast and bird, vegetable and rock - all classes of things and beings - are linked together and attracted to each other with a chord of harmony. If one being or thing, however apparently useless, were missing in this universe of endless variety, it would be as it were a note missing in a song. As Sa'adi says: 'Every being is born for a certain purpose, and the light of that purpose is kindled within his soul'. All famines, plagues and disasters such as storms, floods, volcanic eruptions, wars and revolutions, however bad they appear to man, are in reality for the adjustment of this universal harmony.

There is a story told in India how once all the inhabitants of a village which had suffered from drought gathered together before the temple of their God, praying that for this year an abundance of rain might fall. A voice from the unseen replied: 'Whatever We do is for the betterment of Our purpose. Ye have no right to interfere with Our work, Oh ye men!' But they again cried for mercy, and continued to do so more persistently. Then came the answer saying: 'Your prayers, fastings and sacrifices have induced Us to grant for this one year as much rain as ye desire'. They all returned home rejoicing. In the autumn they worked vigorously on their farms, and after having prepared the ground and sown the seed they prayed for rain. When they considered that sufficient had fallen they again had recourse to prayer, and the rain ceased. In this way an ideal crop of corn was produced and all the inhabitants of that country made merry over it.

This year more crop was grown than ever before. After the crops were gathered in however, all those who ate the corn died and many were the victims. In perplexity they again sought the God bowing low before the temple, crying: 'Why hast Thou shown such wrath to us, after having shown so great a mercy?' The God replied: 'It was not Our wrath, but your folly for interfering with Our work. We sometimes send a drought, and at other times a flood, so that a portion of your crops may be destroyed. But We have Our reasons for so doing, for in this way all that is poisonous and undesirable in them is also destroyed, leaving only what is beneficial for the preservation of your life'.

The villagers prostrated themselves in humble prayer, saying: 'We shall never again try to control the affairs of the universe. Thou art the Creator, and Thou art the Controller. We are Thine innocent children, and Thou alone knowest what is best for us'. The Creator knows how to control His world, what to bring forth, and what to destroy.

There are two aspects of individual harmony: the harmony between body and soul, and the harmony between individuals.

The soul rejoices in the comforts experienced by the external self, yet man becomes so engrossed in them that the soul's true comfort is neglected. This keeps man dissatisfied through all the momentary comforts he may enjoy, but not understanding this he attributes the cause of his dissatisfaction to some unsatisfied desire in his life. The outlet of all earthly passions gives a momentary satisfaction, yet creates a tendency for more. In this struggle the satisfaction of the soul is overlooked by man who is constantly busied in the pursuit of his earthly enjoyment and comfort, depriving the soul of its true bliss. The true delight of the soul lies in love, harmony and beauty, the outcome of which is wisdom, calm and peace; the more constant they are the greater is the satisfaction of the soul.

If man in his daily life would examine every action which has reflected a disagreeable picture of himself upon his soul and caused darkness and dissatisfaction, and if on the other hand he would consciously watch each thought, word or deed which had produced an inward love, harmony and beauty, and each feeling which had brought him wisdom, calm and peace, then the way of harmony between soul and body would be easily understood, and both aspects of life would be satisfied, the inner as well as the outer. The soul's satisfaction is much more important than that of the body for it is more lasting. In this way the thought, speech and action can be adjusted, so that harmony may be established first in the self by the attunement of body and soul.

The next aspect of individual harmony is practiced in one's contact with another. Every being has an individual ego produced from his own illusion. This limits his view which is led in the direction of his own interest; and he judges of good and bad, high or low, right or wrong in relation to himself and others through his limited view, which is generally partial and imaginary rather than true. This darkness is caused by the overshadowing of the soul by the external self. Thus a person becomes blind to his own infirmities as well as to the merits of another: the right action of another becomes wrong in his eyes and the fault of the self seems right. This is the case with mankind in general, until the veil of darkness is lifted from his eyes.

The nafs, the ego of an individual, causes all disharmony with the self as well as with others, thus showing its unruliness in all aspects of life. The lion, the sovereign among all animals, most powerful and majestic, is always unwelcome to the inhabitants of the forest, and he is even unfriendly to his own kind. Two lions will never greet one another in a friendly way, for their nafs is so strong. Although the lion is the ruler of all other animals, he is a slave to his own passions which make his life restless. The nafs of herbivorous animals such as sheep and goats is subdued; for this reason they are harmless to one another, and are even harmonious enough to live in herds. The harmony and sympathy existing among them makes them mutually partake of their joys and sorrows, but they easily fall a victim to the wild animals of the forest. The masters of the past, like Moses and Muhammed, have always loved to tend their flocks in the jungles, and Jesus Christ spoke of himself as the Good Shepherd, while St. John the Baptist spoke of the Lamb of God, harmless and innocent, ready for sacrifice.

The nafs of the bird is still milder; therefore upon one tree many and various kinds can live as one family, singing the praise of God in unison, and flying about in flocks of thousands. Among birds are to be found those who recognize their mate and who live together harmoniously, building the nest for their young, each in turn sitting on the eggs and bearing their part in the upbringing of their little ones. Many times they mourn and lament over the death of their mate.

The nafs of the insects is still less; they walk over each other without doing any harm, and live together in millions as one family without distinction of friend or foe. This proves how the power of nafs grows at each step in nature's evolution, and culminates in man, creating disharmony all through his life unless it is subdued, producing thereby a calm and peace within the self, and a sense of harmony with others.

Every human being has an attribute peculiar to his nafs. One is tiger-like, another resembles a dog, while a third may be like a cat, and a fourth like a fox. In this way man shows in his speech, thoughts and feelings the beasts and birds, and the condition of his nafs is akin to their nature; at times his very appearance resembles them. Therefore his tendency to harmony depends upon the evolution of his nafs. As man begins to see clearly through human life, the world begins to appear as a forest to him, filled with wild animals, fighting, killing and preying upon one another.

There are four different classes of men who harmonize with each other in accordance with their different states of evolution: angelic, human, animal and devilish.

The angelic seeks for heaven, and the human being struggles along in the world. The man with animal propensities revels in his earthly pleasures, while the devilish man is engaged in creating mischief, thereby making a hell for himself and for others. Man after his human evolution becomes angelic, and through his development in animality arrives at the stage of devil.

In music the law of harmony is that the nearest note does not make a consonant interval. This explains the prohibition of marriage between dose relatives because of the nearness in merit and blood. As a rule harmony lies in contrast. Men fight with men and women quarrel with women, but the male and the female are as a rule harmonious with each other and a complete oneness makes a perfect harmony.

In every being the five elements are constantly working, and in every individual one especially predominates. The wise have therefore distinguished five different natures in man according to the element predominant in him. Sometimes two elements or even more predominate in a human being in a greater or lesser degree.

The harmony of life can be learned in the same way as the harmony of music. The ear should be trained to distinguish both tone and word, the meaning concealed within, and to know from the verbal meaning and the tone of the voice whether it is a true word or a false note; to distinguish between sarcasm and sincerity, between words spoken in jest, and those spoken in earnest; to understand the difference between true admiration and flattery; to distinguish modesty from humility, a smile from a sneer, and arrogance from pride, either directly or indirectly expressed. By so doing the ear becomes gradually trained in the same way as in music, and a person knows exactly whether his own tone and word, as well as those of another, are false or true.

Man should learn in what tone to express a certain thought or feeling as in voice cultivation. There are times when he should speak loudly, and there are times when a soft tone of voice is needed; for every word a certain note, and for every speech a certain pitch is necessary. At the same time there should be a proper use of a natural sharp or flat note, as well as a consideration of key.

There are nine different aspects of feeling, each of which has a certain mode of expression:

- mirth: in a lively tone

- grief: in a pathetic tone

- fear: in a broken voice mercy - in a tender voice

- wonder: in an exclamatory tone

- courage: in an emphatic tone

- frivolity: in a light tone

- attachment: in a deep tone

- indifference: in the voice of silence.

An untrained person confuses these. He whispers the words which should be known, and speaks out loudly those which should be hidden. A certain subject must be spoken in a high pitch, while another requires a lower pitch. One should consider the place, the space, the number of persons present, the kind of people and their evolution, and speak in accordance with the understanding of others, as it is said: 'Speak to people in their own language'. With a child one must have childish talk, with the young only suitable words should be spoken, with the old one should speak in accordance with their understanding. In the same way there should be a graduated expression of our thought, so that everybody may not be driven with the same whip. It is consideration for others which distinguishes man from the animals.

It must be understood that rhythm is the balance of speech and action. One must speak at the right time, otherwise silence is better than speech: a word of sympathy with the grief of another, and a smile at least when another laughs. One should watch the opportunity for moving a subject in society, and never abruptly change the subject of conversation, but skilfully blend two subjects with a harmonious link. Also one should wait patiently while another speaks, and keep a rein on one's speech when the thought rushes out uncontrollably, in order to keep it in rhythm and under control during its outlet. One should emphasize the important words with a consideration of strong and weak accent. It is necessary to choose the right words and mode of expression, to regulate the speed and to know how to keep the rhythm. Some people begin to speak slowly and gradually increase the speed to such an extent that they are unable to speak coherently. The above named rules apply to all actions in life.

The Sufi, like a student of music, trains both his voice and ear in the harmony of life. The training of the voice consists in being conscientious about each word spoken, about its tone, rhythm, meaning and the appropriateness for the occasion. For instance the words of consolation should be spoken in a slow rhythm, with a soft voice and sympathetic tone. When speaking words of command a lively rhythm is necessary, and a powerful distinct voice.

The Sufi avoids all unrhythmic actions; he keeps the rhythm of his speech under the control of patience, not speaking a word before the right time, not giving an answer until the question is finished. He considers a contradictory word a discord unless spoken in a debate, and even at such times he tries to resolve it into a consonant chord. A contradictory tendency in man finally develops into a passion, until he contradicts even his own idea if it be propounded by another.

In order to keep harmony the Sufi even modulates his speech from one key to another; in other words, he falls in with another person's idea by looking at the subject from the speaker's point of view instead of his own. He makes a base for every conversation with an appropriate introduction, thus preparing the ears of the listener for a perfect response. He watches his every moment and expression, as well as those of others, trying to form a consonant chord of harmony between himself and another.

The attainment of harmony in life takes a longer time to acquire and a more careful study than does the training of the ear and the cultivation of the voice, although it is acquired in the same manner as the knowledge of music. To the ear of the Sufi every word spoken is like a note which is true when harmonious and false when inharmonious. He makes the scale of his speech either major, minor or chromatic as occasion demands, and his words - either sharp, flat or natural - are in accord with the law of harmony. For instance, the straight, polite and tactful manner of speech is like his major, minor or chromatic scale, representing dominance, respect and equality. Similarly he takes arbitrary or contrary motions to suit the time and situation by following step by step, by agreeing and differing, and even by opposing, and yet keeping up the law of harmony in conversation. Take any two persons as two notes; the harmony existing between them forms intervals either consonant or dissonant, perfect or imperfect, major or minor, diminished or augmented, as the two persons may be.

The interval of class, creed, caste, race, nation or religion, as well as the interval of age or state of evolution, or of varied and opposite interests shows the law here distinctly. A wise man would be more likely to be in harmony with his foolish servant than with a semi-wise man who considers himself infallible. Again it is equally possible that a wise man be far from happy in the society of the foolish, and vice versa. The proud man will always quarrel with the proud while he will support the humble. It is also possible for the proud to agree on a common question of pride, such as pride of race or birth.

Sometimes the interval between the disconnected notes is filled by a middle note forming a consonant chord. For instance the discord between husband and wife may be removed by the link of a child, or the discord between brothers and sisters may be taken away by the intervention of the mother or father. In this way, however inharmonious two persons may be, the forming of a consonant chord by an intervening link creates harmony. A foolish person is an unpliable note whereas an intelligent person is pliable. The former sticks to his ideas, likes, dislikes and convictions, whether right or wrong, while the latter makes them sharp or flat by raising or lowering the tone and pitch, harmonizing with the other as the occasion demands. The key-note is always in harmony with each note, for it has all notes of the scale within it. In the same way the Sufi harmonizes with everybody, whether good or bad, wise or foolish, by becoming like the key-note.

All races, nations, classes and people are like a strain of music based upon one chord, when the key-note, the common interest, holds so many personalities in a single bond of harmony. By a study of life the Sufi learns and practices the nature of its harmony. He establishes harmony with the self, with others, with the universe and with the infinite. He identifies himself with another, he sees himself, so to speak, in every other being. He cares for neither blame nor praise, considering both as coming from himself. If a person were to drop a heavy weight, and in so doing hurt his own foot, he would not blame his hand for having dropped it, realizing himself in both the hand and the foot. In like manner the Sufi is tolerant when harmed by another, thinking that the harm has come from himself alone. He uses counterpoint by blending the undesirable talk of the friend and making it into a fugue.

He overlooks the fault of others, considering that they know no better. He hides the faults of others, and suppresses any facts that would cause disharmony. His constant fight is with the naf, the root of disharmony and the only enemy of man. By crushing this enemy man gains mastery over himself; this wins for him mastery over the whole universe, because the wall standing between the self and the Almighty has been broken down.

Gentleness, mildness, respect, humility, modesty, self denial, conscientiousness, tolerance and forgiveness are considered by the Sufi as the attributes which produce harmony within one's own soul as well as within that of another. Arrogance, wrath, vice, attachment, greed and jealousy are the six principal sources of disharmony. Nafs, the only creator of disharmony, becomes more powerful the more it is gratified, the more it is pleased. For the time being it shows its satisfaction at having gratified its demands, but soon after it demands still more until life becomes a burden. The wise detect this enemy as the instigator of all mischief, but everybody else blames another for his misfortunes in life.